Horace Moore-Jones’ Story

Horace Moore-Jones’ story has many nooks and crannies, much more to explore, and some varying details in contemporary biographical accounts. The following summary includes invaluable records and insights from his descendants.

Forgotten Waikato hero – Waikato Times

Origins

Horace was born in 1868 (or 1869) at Malvern Wells, Worcestershire, England. He came to New Zealand with his parents on the barque Glenlora in 1885, the third of 10 children in the Jones family, the move prompted by his father’s bankruptcy. His elder brother Garner’s diary on the trip is held in Auckland War Memorial Museum.

Father David Millichamp Jones carried the names of both parents John Jones and Harriet Millichamp, and in the new country the large family became ‘Moore-Jones’ in response to the tag ‘too many Joneses’ or ‘not more Joneses’.

Further reading: Moore-Jones Family Background

David (1835-1926) was an engineer and wife Sarah Anne Garner (1839-1929) a schoolteacher. She soon became Principal of the new Remuera Ladies College in Portland Road which expanded to Cleveland House, a turreted mansion in Garden Road where she remained in charge until 1923. This was also the Moore-Jones family home, to which Horace would return again and again.

Move to Sydney

James Mack wrote that Horace realised early his vocation was in art, soon married his Auckland tutor and notable portrait painter and sculptor Anne Dobson, and moved to Sydney. At the time, Mr (and Mrs) Jones felt Australia offered “a life of artistic endeavour would be more rewarding”, away from New Zealand’s “confined cultural climate” – although there would be regular returns across the Tasman. By now he was using his expansive name ‘Horace Millichamp Moore-Jones’.

Horace exhibited with the Art Society of New South Wales 1892-1905 and established himself as a successful painter of portraits and allegorical works. Also would come his initial foray into war art as the Boer War 1899-1902 drew in both New Zealand and Australian colonial troops. He presented his oil painting of ‘The departure of the Ninth Contingent from New Zealand for the South African War’ in 1902 to the Auckland Art Gallery.

Family tragedy interrupted Horace’s personal life: only one of their three children survived, and then his influential wife Anne died on 7 June 1901, leaving their toddler Norma to his care. This daughter would die in June 1921 aged 22, a few months before her famous father. He is buried beside her in Auckland’s Purewa Cemetery, in 1944 joined by 2nd wife Florence.

New wife, new family, new life

Horace married Florence Emma Mitchell at Bellambi a suburb of Wollongong in New South Wales on 29 November 1905. A newspaper clipping suggests a society wedding for the ‘well-known Sydney artist’, followed by a honeymoon at the seaside tourist centre of Kiama. The couple had three children: Amy (known as Puti) in 1906, Paul in 1909, with Sara Chloe a post-war baby born in 1919.

By 1908, the young family was back in Auckland, Horace to a teaching role at his mother’s Ladies’ College, and exhibiting with the Auckland Society of Arts. In 1912 he travelled to London, enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art, and joined Pearson’s Magazine as a staff artist. The First World War called him in 1914, delaying his return home to New Zealand until late 1916.

A family photograph taken in Auckland of Norma with Puti and Paul could be a reminder to be sent to an absent father. Circa 1913-14? Paul (born in 1909) appears under 5years, Puti (1906) perhaps 8, Norma (1896?) in her later teens?

London and Paris

In 1912, “the call of the art world of London and Paris could not be denied” and Horace left his young family at home to enrol at London’s Slade School to study under notable painters such as Frank Brangwyn, Philip Lazlow, Quiller Orchardson and Orpen. After a “brief sojourn” in Paris he joined Pearson’s Magazine as staff artist and book illustrator. War was looming in Europe.

Maori Connections

Maori and marae scenes also featured in Horace’s post-war paintings, illustrating his long-term interest in the Maori part of the nation.

Makereti Papakura

Horace’s life intersected with that of famous Te Arawa guide, socialite and scholar Maggie (Makereti) Papakura (1872-1930) who had also named herself – after the Whakarewarewa geyser. They may have met in Sydney before Horace’s 1908 return to Auckland.

Further reading: Makereti Papakura

Maggie’s concert party, in London for the 1911 coronation of George V, the Festival of Empire and a follow-on music hall tour, became stranded “their manager having absconded with what profits there were”. Horace with his “impetuous philanthropy” hosted them in his studio, found them jobs as models, and sold some of his paintings for their return fares back to New Zealand.

Maggie presented him with a korowai which would stay in the Moore-Jones family until its gifting by daughter Puti to the Northland Regional Museum in 1986, and subsequently to Rotorua’s Museum.

Maggie soon returned to England to marry wealthy Oxford landowner Richard Staples-Browne. She set up “the New Zealand Room” in her North Oxford house for her rich collection of Maori artefacts, clothing and carvings, and held a weekly ‘salon’ for “budding anthropologists, colonial students, and intrigued travellers. And she enrolled in Oxford University for a Bachelor of Science degree in Anthropology, to die suddenly in 1930.

In 1938 her thesis ‘The Old Time Maori’ was accepted and published posthumously, winning her recognition for the first comprehensive account of Maori life by a Maori scholar. The University of Waikato’s Ngahuia Te Awekotuku wrote the introduction to the 1986 reprint – the front cover featuring the korowai Maggie gifted to Horace as a reminder of their London friendship and his support.

Korowai Exhibited

Puti Kingdon died in 1998. Her father’s korowai cloak – gifted to her local museum at Whangarei and passed on to Rotorua Museum in 1987 – was brought to Waikato Museum for exhibition during the public celebration of the naming of Sapper Moore-Jones Place on 30 November 2012. Governor-General Sir Jerry Mateparae and Moore-Jones’ family members had a close-up and personal view.

Sir Maui Pomare

Among Makereti Papakura’s prominent friends was Maori politician and doctor Sir Maui Pomare (1876-1930) and he became a regular visitor to the Moore-Jones’ Auckland home. He also became Amy’s godfather and the architect of her own name-change. Pomare affectionately called her ‘Puti’ and she formally changed her name to this by deed poll as soon as she was legally able (circa 1927).

In later life she would proudly attest her heritage – ‘born an Aussie, lived in New Zealand, and had a Maori name’. (Grand-daughter Cherry Barnaby 2012).

Along with Maori pioneers Sir Apirana Ngata and Sir Peter Buck, Pomare tested barriers in politics and health, and agitated for Maori war service and the Maori Battalion. History’s mists part briefly to suggest he and Horace probably met off-shore, perhaps in London with Maggie in 1912 or during the early stages of WWI. An earlier date is indicated by the godparent role and Puti’s 1906 birthday.

Horace’s 1918 portrait of Sir Maui hangs in Parliament’s Maori Affairs Committee Room Wellington as a reminder of his long service as MP for Western Maori initially as an independent and then with William Massey’s Reform Party (1911-1930).

Gallipoli

In London in 1914 with war declared, Horace enlisted (5 October). He was tall and well-built, and gave an amended birth year of 1879, dropping a decade by cropping and colouring his hair and moustache to indicate 35years rather than his 47. He gave his occupation as artist.

Horace joined the New Zealand Engineers of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) British section as a sapper, trained briefly with other expat New Zealanders and Australians and shipped out to Cairo Egypt to join the encamped expeditionary force already there. The New Zealanders refused the title Australasian for the combined Army Corps which became the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps and shortly the ANZACs.

First Anzac troop landing

On 25 April 1915, Horace was among the first fateful troop landing at Anzac Cove on the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey to begin the bloody First World War campaign we now know simply as ‘Gallipoli’ and commemorated annually on Anzac Day.

Horace’s own words:

“To a man like myself who had never been under fire, there was a curious anticipation – it certainly wasn’t fear – as we were transferred, all the time under fire, first from the transports to the torpedo boats, and from the torpedo boats to the horse punts. Just as we were about to land, the first burst of shrapnel came knocking out good fellows here and there. And then the landing! Some men jumped into the water where they were beyond their depths and were drowned. A moment later we were charging up the beach. Most of us had never seen death. It was curious, with pals wounded and dead all around, how soon one adapted himself to the whole grim business. One became inured to it almost at once.” (WSA, The Weekly Press, August 16, 1916)

He later wrote:

“We lived with death all round us. We lived facing plateaus covered with one’s dead comrades whose faces had grown black – and the overpowering sickening stench. And what it meant to sit eating one’s bread and jam surrounded by millions of flies which had been bred on dead bodies.”

Enemy positions sketched

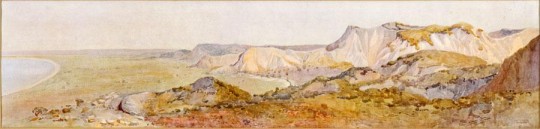

From that disastrous arrival, he turned to his art to record what he saw. Observed sketching and verified as an artist, he was soon assigned to draw enemy-held territory by ANZAC Commander Lieutenant General Sir William Birdwood to make up for the lack of maps. He was attached to GHQ’s Printing Section and his topographical details were judged “an invaluable aid for planning operations and defence, and were used to illustrate official dispatches” (AWMM).

Their use to calculate enemy positions and targets were important in the wake of military decisions that had so endangered the soldiers in this harsh battlefield.

The unofficial war artist was also dispatched personally to the Intelligence Branch of the Egyptian War Office in Cairo to “superintend” the reproduction of some of his drawings for Egypt’s Survey Department Records. (GHQ pass 26.10.1915).

And later, Horace’s work was acclaimed as a record of the Gallipoli Campaign, with press suggestions that freedom from any official oversight probably accounted in part for the paintings’ high artistic merit.

The soldiers had been landed on the wrong beach at Gallipoli but under Birdwood’s leadership they showed great courage and endurance, too ill-equipped to overcome the obstacles that confronted them. The evacuation would start in December, shortly after Horace was shipped back to Britain.

Birdwood requested that the position held by them be known as Anzac and that the place where most of them had landed on 25 April be known as Anzac Cove. Those who fought there were soon called Anzacs, and recognised officially with a small brass ‘A’ on each shoulder of their uniforms.

Moore-Jones’ Gallipoli Series

Nearly a century later, the actions of the Anzacs at Gallipoli are among the world’s enduring legends and the site in Turkey a tourist magnet.

Horace Moore-Jones’ Gallipoli watercolours are the Anzac legacy from his extraordinary descriptive skills. Often under extremely hazardous conditions, the soldier artist crawled through trenches and behind enemy lines, even lifted off in a balloon to trace the topographical intricacy of the bloody battlefield for the artillery and other military purposes, using pencils and watercolour.

After seven months on the peninsula, wounded in his right hand and exhausted, he was invalided back to England a few weeks before the Allies evacuated.

While recuperating he developed a series of 75 pieces from his initial sketches and observations. Former NZ Prime Minister and High Commissioner Sir Thomas Mackenzie arranged an exhibition at New Zealand House and thence upon Royal command to Buckingham Palace where “he discussed his work at length with His Majesty King George V”, along with the Queen, Prince Albert and Princess Mary (Evening News, 19 April 1916).

Public acclaim

London newspaper reports – recalled in the 1964 WSA booklet – were very favourable:

“The exhibition…should be visited by everyone who wishes clearly to understand the nature of the difficulties which confronted the heroic soldiers in Gallipoli.” (Evening News,19 April 1916)

“…This memento of a great episode should be prized not only by Australians and New Zealanders but also by people throughout the Empire.” (Morning Post, 11 April 1916)

“They enable one to see better than a photograph the kind of country the troops had to contend with …Sapper Moore-Jones is no amateur but a trained artist whose topographical drawings have the beauty of precision.” (The Times, 15 April 1916)

“The military artist is himself the eye of the Army, the eye that sees the intricacy of gorge and gully, hill and plain, and conveys its message by brain and hand so that the commander and men may understand what lies before them, learning more clearly from the pictured representation of the country than they could by a wealth of words. Apart from the high artistic merit of these sketches, apart from their intrinsic, historic and romantic value, they have a further interest for many of them were drawn under shell fire…” (The Evening Standard and St James Gazette)

“He shows a breadth and freedom of treatment and a feeling for colour that will recommend his work to art lovers…” (The British Australian, 13 April 1916)

And there was expectation:

‘How desirous a possession for future generations of Maorilanders would be these world famous Gallipoli pictures.’

Horace received “some handsome offers” for the complete set but refused, confident the New Zealand Government would seek them for the National Collection. James Mack’s chronology says negotiations opened in July-August that year (1916) and there was a second exhibition of the works at the home of prominent portrait painter Hugh Goldwin Riviere (1869-1956). In October the soldier artist was discharged, classified as unfit for battle duties, and repatriated home to New Zealand, with his Gallipoli collection.

The Dominion Museum, already recognising public response to Gallipoli, had sought support to gather records for a war collection from William Massey’s Reform-Liberal Coalition government (1915-1919). But “the wartime government considered war art unnecessary and expensive” unlike Britain, Canada and Australia who saw value in documenting their countries’ activities and for propaganda. Sir Maui Pomare’s role in this issue at this time – if any – has not been researched.

It was mid-1918 before New Zealand had an official war art programme. In London Sir Thomas Mackenzie arranged two official war photographers, and Major General Andrew Russell, the Commander in France, seconded the first official artists from the ranks of the NZEF “writing stories, composing poems and songs, sketching, and drawing cartoons or caricatures”.

The Famous Painting – “Man with a Donkey”

WHY HAMILTON?

Public popularity

In 1918, the Waikato welcomed Horace as he continued his lecture tour, and his public popularity ensured his place in Hamilton history. Because so many people wanted his “facsimiles” when he exhibited his Gallipoli water colours in the town, he was at last persuaded to come to Hamilton to teach. He set up a studio in Frear’s Building in Garden Place for his portrait commissions and private teaching, and became Hamilton High School’s founding art master, returning to his Auckland home at weekends.

Soon his art works ‘lined the school corridors’, according to Hamilton High School records unearthed for the school centennial in 2011. Horace ‘built up the school art collection’ with founding Principal Eben Wilson, and included his own watercolours and black and white drawings.

It’s not now known what happened to these, nor ‘the set’ of Moore-Jones Gallipoli paintings called ‘pictures and prints’ and presented by the Old Boys’ Association before his death, ‘the school to arrange their framing’.

On which wall?

The disappearance of these along with the Nathan gifts to the town council after his death presumes not destruction, but rather evidence of the artist’s popularity and the lengths some might go to ensnare his work in the privacy of their own homes. The inclination is to suspect private desire overwhelmed public accountability and that somewhere someone knows the truthful providence of the Moore-Jones works on the wall.

In Horace’s heyday, Hamilton had a population of around 11,000, a town small enough to know and big enough to hide in.

Prolific and Popular

Recollections from family and friends passed down through the years confirm Horace a prolific artist, popular among the arts community and further afield, a talented celebrity, quick and skilled at converting his observations, generous with his time teaching and mentoring others – including Ida Carey (1891-1982) encouraged by him to flee to Sydney to study and make a name for herself.

Puti Kingdon, 12 when her father died, recalled the pencil and pastel drawings of friends, relatives and children that Horace often gave away, although family members were retentive. (Julie Middleton interview, Sunday Star, 1989)

Dr & Mrs E.T. Rogers who produced two politician sons – Dr Denis mayor of Hamilton 1959-1968 and Dr Anthony/Rufus Hamilton East MP 1972-1975 – were creativity stalwarts and included nine of Horace’s works from their personal collection in the 1964 WSA retrospective alongside the family-held. The Rogers’ included a 1921 portrait of Denis and a Gallipoli landscape. Denis’ daughter Sylvia Calnan suggests the doctors and the artist developed a trade relationship along with friendship, paintings for health care. (TOTI 2012)

There were also significant commissions such as the Pomare portrait, his poignant scenes of Maori life, landscapes of Auckland, and his family. He also turned his artist hands to sculpture, some examples retained within the family (Barnaby, TOTI 2012)

Heroic death

On Monday 3 April 1922, Horace Moore-Jones died a hero, returning twice into a fearsome inferno to rescue women trapped by the early morning hotel fire, until rescued himself by firemen from the roof-top, his own life leaving him hours later.

By all accounts he was a most popular and talented man, with celebrity status across New Zealand originating out of his Gallipoli lectures and descriptive art illustrating a nation-making event known as The Great War. A community man, fostering interest in and love for the arts, teaching the young.

Further insight into Horace Moore-Jones the man comes from a poem “Values” found among his Gallipoli papers and published by Hamilton High School in a special edition of Journal July 1922 commemorating Moore-Jones, a man known throughout New Zealand “from one end to the other”. The poem “sums up his whole life, a life of integrity and value”:

Values

What does it matter who sung the song, if only the song was sung,

What does it matter who did the deed, be he old in years or young?

What does it matter who ran the race, so long as the race was run?

And why should the winner be proud of himself, because it was he who won?

The one who ran, and did not win, did he not do his best?

If he ran to the measure of his strength, what matters all the rest?

If the song was sweet, and helped a while, what matter’s the singer’s name?

The worth is in the song itself, and not in the world’s acclaim.

O hearts bowed down with sense of loss because ye did not win,

If ye ran your best (I’say your best) ye, too, have “entered in”

The song, the race, the deed are one, if each is done for love,

Love of the weak and not love of self, and the score is kept above.