The Famous Painting ‘Man with a donkey’

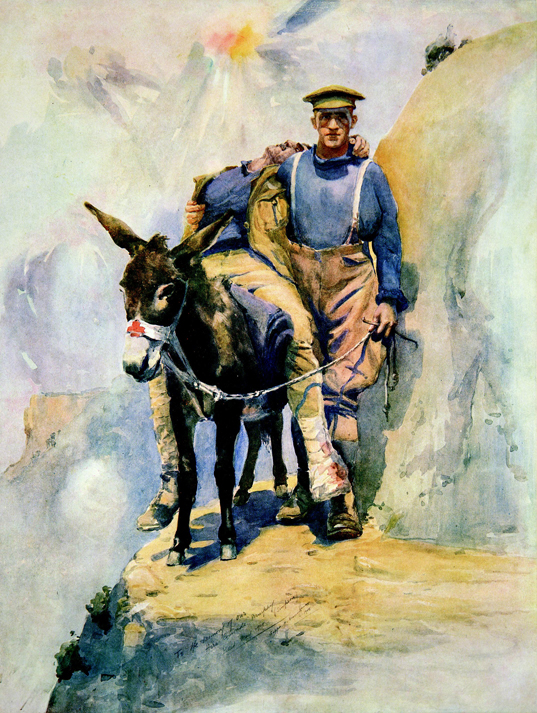

Horace painted his most famous Gallipoli work back in Auckland after visiting Dunedin during the RSA tour. He dedicated it to “our hero comrade Murphy [Simpson]” – writing this by hand on the watercolour. He would paint several versions, identifiable from slight differences in composition and treatment and all of them commonly known as ’Murphy and his donkey’, ‘Simpson and his donkey’, Henderson and his donkey’, and simply ‘Man with a donkey’. There would also be lithograph copies or ‘facsimiles’ (and more on this to come).

Names, numbers, and origins of this work have all been the subject of decades of argument and banter in both New Zealand and Australia, and elsewhere. This story continues to jostle memories and minds, backwards tracking for argued details.

What is clear is that in Dunedin in 1917 Horace was shown a photograph of a field medic using a donkey to carry a wounded soldier to safety from the Gallipoli battle zone. This came in response to his lecture, and to Horace’s descriptive recollections, the sights he recalled.

The famous ‘Man with the Donkey’ watercolour – NZ’s with the artist’s notation lower centre

Douglas Seymour’s story

In 1917 Douglas Seymour was the new RSA General Secretary and manager of Horace’s fund-raising tour, travelling with him for six weeks in the South Island – “resulting in a comfortable credit balance which relieved anxiety for the executive”. He told his story half a century later in the foreword to the 1964 WSA exhibition catalogue by which time he was a prominent Hamilton lawyer and co-founder of the University of Waikato.

Seymour wrote that the artist’s “word-picture” of the scene Horace had witnessed of the donkey carrying wounded men from Shrapnel Gully to Anzac Cove appealed to his audience and “he decided to supplement it with a wash-drawing, which he then did.” Prompted by the photograph of the scene he had described, shown to him the next day by the soldier photographer’s brother, and quickly sketched by Horace.

Private James Gardner Jackson’s photograph was of his New Zealand Medical Corps comrade Private Richard Henderson of Waihi and not the Australian Simpson later claimed.

The Photographer’s Story

As Simpson became the Aussie Anzac icon, Jackson attempted to put the record straight. But he got nowhere and in the 1930s decided against detracting from ‘the great name Simpson had’.

John Simpson Kirkpatrick had been killed three weeks into the Gallipoli campaign, and the ‘donkey man’ legend ingrained, the hero Simpson widely identified for his singing and whistling as he had gone about his rescue duties; known by his mother’s maiden name used when he enlisted (but that’s yet another tale), his story spread and grown.

A Picture of Bravery – New Zealand Herald

In 1961, Jackson again went public to confirm that the stretcher bearer was Henderson, and not Simpson. “I met Dick Henderson on the way from Walkers to the cove with his patient,” he said in a letter to the Weekend. “I said, `hold it a minute and I’ll snap you, Dick’.” He also revealed that Horace Moore-Jones used ‘painters’ licence’ by placing the soldiers on a precipice, rather than where the picture was taken, between Anzac Cove and Walkers Ridge. And that he had taken several photographs of the scene.

Historic Simpson’s donkey print fails to sell – National

Today the negatives are held in the Hocken Collection with Jackson’s diaries and papers, and with the model used for Horace’s ‘Man and Donkey’.

Waikato Times publicity about the TOTI project on Anzac Day 2012 flushed out an autographed copy of the photograph from Te Awamutu man Noel Johnson, gifted to his mother Edna Johnson (nee Parker) by family friend Henderson just a few months before his death.

Gallipoli photograph proves New Zealand link – Waikato Times

The Henderson Story

‘Dick’ Henderson who was 19 at Gallipoli, went on to the Western Front and won the Military Medal at the Battle of the Somme in 1916 for repeatedly bringing in wounded men under heavy shellfire. He was later exposed to mustard gas at the battle of Passchendaele and, after recuperating at a hospital in France, was sent home just before the war’s end in 1918, left with badly damaged lungs, and totally blind by 1934. He died in 1958.

His link with the Moore-Jones painting began to emerge in 1950: “I never really worried about the legend, but I’m getting old now and I would like the full story told before I die.”

The RSA picked up the Simpson-Henderson debate with their memorial bronze of the Jackson photograph commissioned for the Wellington War Memorial in 1990, with son Ross Henderson of Auckland as guest of honour.

Anzac medic’s bravery marked – National

The Murphy and Henry Story

In a further twist to the story, the four-legged Gallipoli ambulance is now also claimed a New Zealand innovation, and Te Kauwhata soldier William Henry with initiating the service using the donkeys (or mules) carrying water to the front-line. One was named ‘Murphy’ – which explains the annotation on Horace’s painting as mule, not a man. Henry was a field medic, training to be a doctor, and awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his work at Gallipoli. His family have gifted their archives to the National Army Museum in Waiouru. (Hamilton’s Nancy Henry – TOTI 2012).

Researchers at the National War Museum confirm the family’s version, that Henry and Murphy were the first Gallipoli rescue team before Simpson and his donkey Duffy. Museum spokeswoman Nicola Bennett says they have ‘uncovered reports that Henry had posed for Horace Moore-Jones’ – perhaps explaining the origin of the artist’s ‘word-picture’ from Doug Seymour’s recollection. Henry the first sighting held in the mind, Henderson’s photograph the model for the painting.

Kiwi claim to legend of Gallipoli heroism – The New Zealand Herald

The Donkey Series

Horace initially painted two ‘originals’ of the donkey service. Family history says he was mindful of the war-time submarine threat and sent them by separate ships to London to Regent Street lithographer W.J. Bryce for reproduction, with instructions to destroy one if both arrived safely. Safe they were, both. While one was returned to Horace in New Zealand, the second was sold (by the lithographer?) to an Australian art gallery for £500 eventually to make its way to the national War Memorial Museum in Canberra with Horace’s other Gallipoli paintings.

The Australian story confirms it in London as the property of the Australian Commonwealth Government, reproduced by the British Historical Section (Military Branch) of the Committee of Imperial Defence in 1926. In the 1960s it was brought back from London to their Prime Minister’s Department through long-term politician Sir John McEwan (1900-1980), Country Party Leader and briefly PM 1968-71. The painting entered the national collection in the 1980s.

Horace’s widow Florence sold the original to the Auckland Commercial Travellers Club in 1926 for £150, although some say it was gifted by her, perhaps recalling that one of the Club’s members Rory O’Moore died with Horace in the 1922 Hamilton Hotel fire. This 100x75cm watercolour is now held on permanent loan to Auckland’s Art Gallery and was exhibited in Hamilton as part of the 1964 WSA retrospective. It’s ceremonially on show each Anzac Day and a poster-size replica continues on prominent display at the club now renamed the Auckland Commerce Club.

Timaru’s Aigantighe Gallery also claims an original, “presented by the South Canterbury Arts Society from the collection of James Maling” (a former mayor) for its opening in 1956 – and still inaccurately named for Simpson and credited as painted in 1915. It’s smaller than both the Auckland and Canberra museum originals – at 36.6 x 29.8cm.

Following Horace’s tragic death in Hamilton, family friends and supporters organised a benefit exhibition for his widow Florence and young children – but there’s no record (yet) found that the works for sale included an iconic donkey.

One was auctioned by Webb’s in 2008 for $110,000 – its providence quoted as ‘gifted by Moore-Jones before he died’.

And, in a mystery currently unsolved, a Mr Nathan in 1923 gifted two of Horace’s paintings to ‘the town of Hamilton’ including ‘a sketch of Murphy the Gallipoli Donkey‘, according to an Auckland Star report that March (below). The donor was likely of the hotel and brewing Nathans involved with the Hamilton Hotel and fire victim Rory O’Moore’s employer. The gifts are not recorded in the borough council minutes of the time, and their whereabouts today unknown.

Today, Waikato Museum has a tiny version of ‘Man and the Donkey’, a reproduction print gifted to the Waikato Museum Society in 1967 by Mrs Frank Herbert, and on display in November 2012 with the Papakura korowai from Rotorua to celebrate Hamilton’s newly named Sapper Moore-Jones Place.

Trust Waikato and Friends of the Museum have gifted three Moore-Jones purchases in recent years and the museum now holds an eight piece collection of the artist’s works. There’s also a copy of the 1917 catalogue booklet from Horace’s RSA lecture tour, and the city Library Heritage section has a copy of the 1964 WSA catalogue.

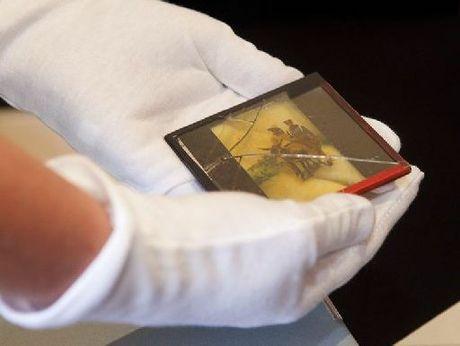

The glass slides

This Waikato collection is now boosted by the extraordinary gift to the people of Hamilton from the Moore-Jones family that day (30 November 2012) and which gives insight into the reproductions of Man with the Donkey. Grand-daughter Cherry Barnaby presented the original glass-slide image of the iconic Anzac painting to Mayor Julie Hardaker, expressing the family’s appreciation of Hamilton’s recognition of Horace and seeking the safekeeping of this Gallipoli ‘treasure’ for the future.

The First Reproductions

Back in 1916 at the time of his London exhibition Horace had reproduction in mind. Hugh Rees printed an elegant publication ‘Sketches made at Anzac’ featuring 10 of Horace’s paintings and a set of glass-slides used for projecting and printing was made of the series. The Regent Street lithographer to whom he would entrust his ‘Man with the Donkey’ twins two years later was commissioned to publish copies “13½ x 10 inches and a three colour process”, for sale at 7/6d (seven shillings & six pence).

Horace used the slides to illustrate his lectures on his 1917 RSA fund-raising tour of New Zealand and RSA clubs were able to use them to print copies – “by impressed amateurs particularly at Christchurch and Papakura” (RSA Review April 1989). His daughter Puti Kingdon presented the slide set to the National Art Gallery but retained the famous donkey which passed on to her daughter Cherry Barnaby and thence to Hamilton City.

This slide also enabled Horace to project the image on to his canvas for hand-painted copies, each one a new ‘original’…just how many remaining history’s secret.

Family members all have copies which they decorate with poppies each Anzac Day and celebrate Horace’s place in their family and in history. (Cherry Barnaby, TOTI 2012)